The River Doubs (rhymes with “dew” – has anybody French ever pondered whether there is any redeeming social value in having a language in which almost half of the letters in any word do nothing but take up space) arises in the Jura Massif near the Swiss border. Eventually, it becomes an on-again, off-again portion of the Canal du Rhone au Rhin(e) (The name of the river has a final “e” in German and English but not in French, which doesn’t much matter since the French wouldn’t pronounce it anyway). The canal connects the Rhine River in the east, on the German border, with the Saone and the Rhone Rivers, running north and south through the center of France, down to the Mediterranean at Marseilles. It’s a beautiful river, with steep gorges on both sides.

Beautiful except when it rains. And the river rises. And gentle barging becomes white water rafting. Then the waterways authority, with eminent good sense, slams shuts the steel doors on the various portes de garde – guard doors that shut off the roaring river sections from the placid canal sections – and navigation comes to a halt.

That is what happened in this, our summer of being adaptable. We were at Montbeliard (don’t pronounce the “t” or the “d,” or you know what, just go ahead and do it; they won’t care), the namesake for brown and white Montbeliard cows (think chocolate Holsteins) and the saucisse de Montbeliard, the Montbeliard sausage, which is entirely porcine and is not made at all from Montbeliard cows but, nonetheless, is the champagne of sausages, the ultimate hot dog. Montbeliard is also the home of the automaker (and bicycle maker) Peugeot. Think French Detroit. But with better food and wine. And no bankruptcy.

We’d been up and down the Rhone au Rhine canal two years ago. Hemmed in by mountains on both sides, it wasn’t bicycle country, at least not for us mortals. We’d had the sense that there was something interesting lurking beyond the river and canal, but we never saw it.

We took the canal closing as an opportunity to see what was over the hills and not too far away. We rented a car from our usual rental company – Europcar – booking it through our usual rental car booking company – AutoEurope, located in Portland, Maine, not all that far from our home north of Boston. For some reason we get better prices going through the U.S. agency, using a U.S. credit card, than by going directly to the French company with a French bank card. Besides, the woman I dealt with over the phone at AutoEurope turned out to live down the street from our daughter Nicole, who lives in Portland. The Montbeliard Europecar agency is located literally at the front door of the massive Peugeot factory that occupies a significant percentage of the landscape around the city. Peugeots are nice cars. We looked forward to renting one. However, excited to have American customers, the rental company bestowed upon us a Ford. As a favor. When we asked they said they didn’t have a Peugeot available. Right. Go across the street and knock on the front door. To show we were not disappointed Sandra explained that she grew up in Dearborn, Michigan, the home of Ford. Dearborn, the Montbeliard of the U.S.

We drove up into the Jura Mountains on the first weekend of August, joining the rest of France on vacation. Living wild and free, we’d made no reservations and had little idea where we would stay for the four nights we hoped it would take for the river to settle down. Our main goal was to learn about, purchase and consume Comte (pronounced “con-tay,” because it is more interesting if the “m” sounds like an “n,” just this once) cheese made in the Jura, among our favorite French cheeses.

We arrived at Salins les Bains, a town named for its salt, recently made a UNESCO World Heritage Site for the historic salt works there. The first stop was the museum of salt. (France has a “museum of . . .” just about everything; somewhere there must be a Museum of Museums). We descended to the underground vaults where over the centuries wells had been dug to deep deposits of salt water. This water was pumped to the surface and run into copper trays. Fires were built under the trays to evaporate the water and salt was shoveled out. Tons and tons and tons of salt for hundreds and hundreds of years, a goodly portion of France’s salt. Today, salt comes from other sources. The town uses the salty water to melt snow on its streets in the winter.

Interesting for sure. But it wasn’t cheese. The hunt continued.

We went to the tourist information office in Salins les Bains and explained that we wanted to stay at a farm. Where they made Comte. The woman thought for a while and said there might be a place. She made a phone call and said, yes, they had a room. Did we want to drive to the farm and see it? Certainly, we replied.

Thus we found la Grange Combaret (www.grange-combaret.com). What had been the farm’s barn until it burned down a few years ago was rebuilt as an auberge, a country inn with four guest rooms and a long dining table. Our second floor room was a shock, huge, new, bright and with a balcony overlooking the rest of the farm. And the herd of 40 Montbeliard milk cows. Sandra was in bovine heaven and made a beeline for the dairy barn, toward which the cows were ambling for their afternoon milking, cow bells tinkling as they strolled down from the pasture. The farmer, Denis, and his son Xavier were milking. Sandra said her grandfather had been a dairy farmer.

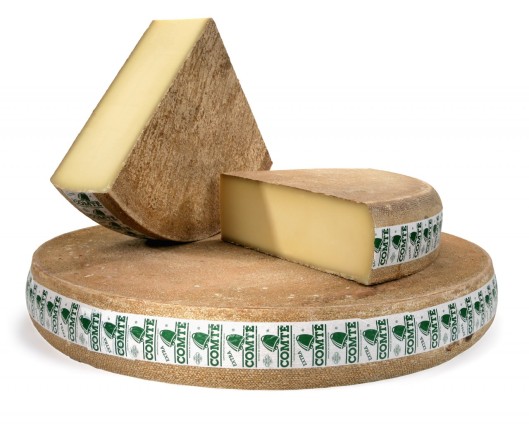

All the farm’s milk goes to the nearby cooperative fruitière (why a cheesemaking operation is called a “fruitière” remains a mystery) where it is made into 50 kilogram (110 pound) wheels of Comte cheese. Each wheel requires 600 liters (160 gallons) of unpasteurized milk – about 30 cows’ daily production. Because Comte production requires so much milk, each town’s farmers pool their production at the fruitière. After a few weeks, the Comte wheels are shipped to the cave de affinage – the aging facility – where the cheese is stored on old pine shelves for anywhere from a few months to several years, where it is regularly rubbed with salt and turned over and over. All this fondling makes Comte special, we were told.

The wheels of Comte are stored in the cheese cellar for up to two years. Does eating a two-year-old unpasteurized milk product worry you? Try it, you’ll like it.

Comte is a hard cheese, much like Gruyere, which is made just over the border in the Swiss town of Gruyere – what an amazing coincidence. The designation Comte is protected, an A.O.C. – Appelation de Origine Controlle – just like champagne that can only come from Champagne, or Montbeliard sausages that can only come from around Montbeliard. Comte has been made this way for centuries and still must be made under strict A.O.C. rules. For example, all the milk must come from Montbeliard cows. Each cow must have at least one hectare (about 2.5 acres) to graze. The cows must graze in the pastures and not be fed hay, except during the coldest winter months when they eat hay made from their regular pasture and the cheese is white rather than the yellow of summer cheese. The high mountain pastures contain 150 or so different grasses and wildflowers that impart rich flavors to the milk. The pastures can only be fertilized with compost produced on the farm with no chemicals. There’s probably a regulation about the size of the cow bells. And maybe the farmer has to milk his cows left handed.

Each fruitière, where the milk is turned into cheese, is owned cooperatively by the local farmers since the Comte standard allows milk to be transported no more than 14 kilometers from farm to fruitière. As a result, each fruitière’s Comte reflects – to use the untranslatable French word that extols most everything local – the terroir of the local pastures. Just as wine from one town in Bourgogne – Burgundy – is distinctively different from wine made from identical grapes in the next town, so Comte cheese made at one fruitièrie is different from the next town’s cheese. Different because milk from different pastures with different blends of grasses and flowers has different flavors. Different because the cheesemaker is different. Different because, being France, each town makes the best Comte. Just ask anybody in the town.

And different because the affinage – the aging process – is different. During affinage hundreds of rounds of cheese are tucked away in caves, stone sheds and special aging vaults. As their time of readiness approaches, the affinage expert – the affineur – goes from wheel to wheel tapping the top of the wheel with a small hammer called a sonde, listening for the sounds. They hear distinctions ordinary mortals don’t hear. (Bringing to mind the time we accompanied Sandra’s father, a professional drummer, to a drum shop in Nashville, Tennessee to shop for a new cymbal. He spent an hour in the shop’s cymbal room, tapping each of the hundreds of cymbals on display. At the end he didn’t buy anything. They didn’t have one with the sound he was looking for, he said). The cheese tells you when it is ready to eat. At least it tells the affineur.

Now this seems like an awful lot of effort for something as straightforward as a piece of cheese. After all, we come from a place where most of what is sold as “cheese” is required by law to include the word “product,” as in “cheese product,” on the label, to distinguish it from a food item that is made entirely from, what shall we say, milk rather than what could be a petrochemical. American cheese technology progressed from the solid brick of cheese to the wonder of presliced cheese to the ultimate luxury of individually wrapped-in-plastic slices of cheese. Flavor has never been a priority when it comes to the cheese product called American cheese. Uniform meltworthiness is a good thing. And texture, which has to be somewhat stretchy.

So Comte was a revelation to us.

We had dinner at the farm one night, chicken raised at the farm drenched in a sauce of, what else, Comte. Think chicken fondue. Think local, as in whatever we ate had originated within sight of the kitchen.

Our four-day cheese expedition was a success. We knew we liked Comte. Now we knew why. Like so much of France, what made it special was a blend of tradition, of expertise, of over the top attention to doing things right. And an added dose of magic.

We returned to the barge. The river settled down and we raced to the end of the canal before the next set of rain storms arrived. We’re safely settled back in the France we know best, Bourgogne, tied to the stone wall in the port at Dijon. We can still buy Comte at the fromagerie in Dijon, but tonight’s cheese will be Epoisse de Bourgogne, described as a pungent unpasteurized cows milk, smear-ripened (meaning it is rinsed in a local liquor) orange cheese made a short ways up the Canal du Bourgogne. At a town called Epoisse. It was Napoleon’s favorite cheese.

That is how France works.

A great post! Thank you.

The post was so much fun that I went to Trader Joe’s and bought some Comte! as close as I could get to what you are doing! any wine suggestions for pairing with Comte?

Again, merci for taking us all along!

We like drinking the local wine with local cheese. Jura white wine goes with Comte. Jura wine is an acquired taste. I acquired the taste after one glass. I then acquired two 5 liter boxes.

Great story and so well put into words!! It really makes me want to visit and stay at La Grange Combaret!

The farm makes a great base for exploring the Jura. And stay for a Saturday night dinner.

Thanks for the tip – that sounds a great plan!

Enjoying your blog – so much so I have nominated you . . . http://jackieparry.com/2014/08/27/a-nomination/ 🙂

What an awesome article. Made me feel like I was right there with you. We took our first barge cruise with the Barge Connection http://www.bargeconnection.com and we had a similar experience. Suffice it to say we ate cheeses we didn’t even know existed and of course, become hooked. There is nothing better in life than to be on a barge cruise, sipping a glass of wine, dining on fine cheese and enjoying that moment with friends and family.